Each year, the monsoon brings both life and destruction to

India. On the one hand, it replenishes rivers, sustains crops, and cools

parched landscapes. On the other, it takes hundreds—sometimes thousands—of

lives, destroys homes, washes away farmland, and leaves families in financial

ruin. Cyclones and cloudbursts add further shocks to an already fragile system.

But beyond nature’s fury, what matters is how governments count, classify, and

compensate these losses.

The Unequal Geography of Loss

When rainfall overwhelms rivers or breaches embankments, the

impacts are never uniform. In Assam, flooding is near-annual, and the damage is

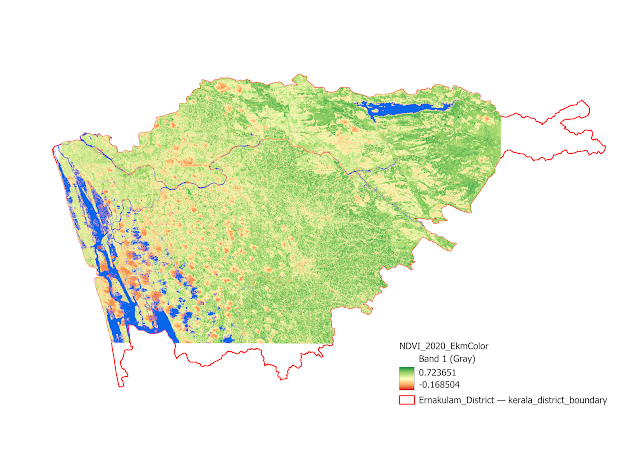

spread across lakhs of hectares of farmland. In Kerala, sudden cloudbursts lead

to landslides that kill entire families in hillside hamlets. In Rajasthan,

swollen rivers destroy houses built precariously near dry riverbeds.

Yet the official narrative often collapses this variety into

raw counts: X deaths, Y hectares submerged, Z houses lost. This simplifies the

reality but also shapes how relief is sought and justified.

Central Relief: Rational or Political?

The Centre’s National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF)

and allocations under the State Disaster Response Fund (SDRF) are meant

to support states in coping with such crises. On paper, allocations are guided

by assessment committees, technical formulas, and Finance Commission

recommendations.

But in practice, questions emerge:

- Do

states ruled by the same party as the Centre get faster approvals or larger

packages?

- Are

losses measured mainly in terms of economic value—which tilts allocations

toward industrialized states with higher-value assets—rather than human

lives or per capita impact?

- Do

politically less influential states lose out because their disasters are

seen as “routine” rather than “exceptional”?

This tension between technical rationality and political

discretion lies at the heart of India’s disaster relief story. India’s federal

design means this tension is not trivial — states depend on the Centre for

extraordinary relief, but the Centre retains discretion in disbursing it.

How the System Works Today

When floods, cyclones, or extreme rainfall strike, relief in India flows

through two channels: the State Disaster Response Fund (SDRF) and the National

Disaster Response Fund (NDRF).

The SDRF is the first line of response. States dip into it

to provide ex gratia compensation for deaths, run relief camps, distribute food

and clothing, or support quick crop and house repairs.

If the disaster overwhelms this capacity, the state

escalates its claim to the Centre. A detailed memorandum goes to the Ministry

of Home Affairs, which then sends an Inter-Ministerial Central Team to inspect

the damage.

What follows is a “norm-based” calculation. Losses are

tallied according to fixed rates: for example, ₹4 lakh for every deceased

person (I shall write about this in another blog to cover VSL), standard

amounts for each hectare of crop destroyed, each damaged house, or each lost

head of livestock.

The final word, however, rests with a High-Level Committee

chaired by the Union Home Minister. This body decides how much of the assessed

claim will actually be sanctioned.

So, India’s system is semi-formulaic: it relies on

standardized norms to quantify loss, but leaves room for political discretion

in the last stage of approval.

What Metrics Should Matter?

Imagine three possible yardsticks:

- Per

capita basis – Relief is proportionate to the number of people

affected or killed.

- Per

hectare basis – Relief considers agricultural losses and rural

livelihoods.

- Asset

value basis – Relief reflects economic value destroyed

(infrastructure, industries, real estate).

Each metric tells a different story. A state with fewer

deaths but higher-value damages may appear to “deserve” more, while another

with widespread human loss but poorer reporting systems may be underfunded. Currently,

relief norms mostly reflect per-unit losses — a fixed sum per life, per

hectare, per house. But should these norms evolve to reflect vulnerability,

inequality, or long-term displacement?

Beyond Numbers: Capacity and Visibility

Another inequality creeps in through administrative capacity.

States with strong disaster management authorities (like Odisha) document

losses more meticulously and secure larger packages. Others, despite suffering

equal or greater hardship, fall behind simply because their reporting is

weaker. Media attention also amplifies certain tragedies while muting others. This

creates a paradox where disaster governance rewards bureaucratic efficiency

rather than sheer human suffering.

Towards an Agenda of Disaster Justice

Rethinking disaster governance in India means asking harder

questions than we usually do. Can we design transparent formulas that weigh

human, ecological, and economic losses on a more equal footing? Should relief

allocations also reflect a state’s vulnerability profile—acknowledging that

Assam’s annual floods or Odisha’s cyclones are not “rare shocks” but recurring

realities?

How do we safeguard against political distortions, ensuring

that the flow of relief in a federal democracy is guided by need rather than

party alignment? And most urgently, can we move beyond treating human lives as

a line item in damage reports, and instead place the dignity and safety of

people at the centre of disaster finance?

India can no longer afford to treat each flood or cyclone as

an “exceptional” event. Climate change is making extremes routine. The

challenge now is to build equity into relief as a recurring responsibility, not

as a one-off act of generosity.

Where to begin the Research

Trying to study these questions, the challenge is both

conceptual and practical. Conceptually, we need to blend disaster justice,

fiscal federalism, and risk governance frameworks. Practically, we must stitch

together diverse datasets: rainfall anomalies from the IMD, fatalities and crop

loss from NDMA and NCRB, and NDRF/SDRF allocations from the Ministry of Home

Affairs and Finance Commission reports.

One possible way to test fairness is through a simple

statistical test, such as a regression model that tests whether central

relief flows actually follow the logic of “need.” For example:

Relief per capita (or per hectare) =

α + β1(Fatalities per capita) + β2(Crop/hectare losses)

+ β3(Population affected) + β4(Political alignment dummy)

+ ϵ

Dependent variable: relief

received per capita or per hectare (state-wise, annually).

Independent variables:

fatalities, crop/hectare losses, affected population, ruling-party alignment,

and possibly GDP per capita or administrative capacity as controls.

Interpretation: A strong

positive coefficient on fatalities/losses would suggest relief follows need. A

significant coefficient on political alignment would indicate a bias favouring

states ruled by the Centre’s party. Weak or insignificant coefficients on human

loss might expose a troubling undervaluation of lives in disaster finance.

Even if the data is noisy, this kind of model can reveal

patterns behind the numbers by turning scattered reports of “bias” into a

structured inquiry.

The gaps in India’s disaster data are real. But precisely

because of these gaps, the politics of relief often hides in plain sight.

To conclude

The monsoon is not going away. Climate change suggests it

may, in fact, intensify rainfall extremes. If central relief remains uneven, whether

for political or technical reasons, the burden will fall disproportionately on

the poorest households, who are least able to rebuild.

Perhaps the next time we hear of “record-breaking rainfall”

or “monsoon devastation,” we should not just ask how many lives were lost—but

also, whose losses will be counted, and whose relief will be delivered. Will

relief in India remain a negotiation of politics and paperwork, or can it

evolve into a transparent system that values lives as much as assets?